Feeding the world with 60m cows

With the enforced downtime of Covid-19, it gives space to reflect on the options we have available to us to feed a projected 10bn+ people by 2050. As followers of Cainthus are aware, we are big believers in the ability of dairy to help mitigate a number of big problems in the world:

1. Dairy is a highly efficient source of complete protein that is proven to combat malnutrition

2. Most of a dairy cow’s diet (~90%) is waste from crop production, mitigating the waste creation of that agricultural sector

3. Cows can produce high quality food on land that is unsuitable for growing human edible crops

4. A well managed manure system can reduce the need for chemical fertiliser, sequester a lot of carbon, restore degraded land, and create a more circular and environmentally friendly crop production system. Manure can also be used as an energy source.

There is a trend with certain Ag Tech start-ups and special interest groups to take the worst traditional agricultural metrics available on the spectrum and use those to justify a new, unproven way of doing things that rely on generous assumptions and projections (we covered this in a previous post called The Bull About Cows). In this post, we will take the best in class metrics for dairy and see what it looks like if we apply those metrics on a more widespread basis.

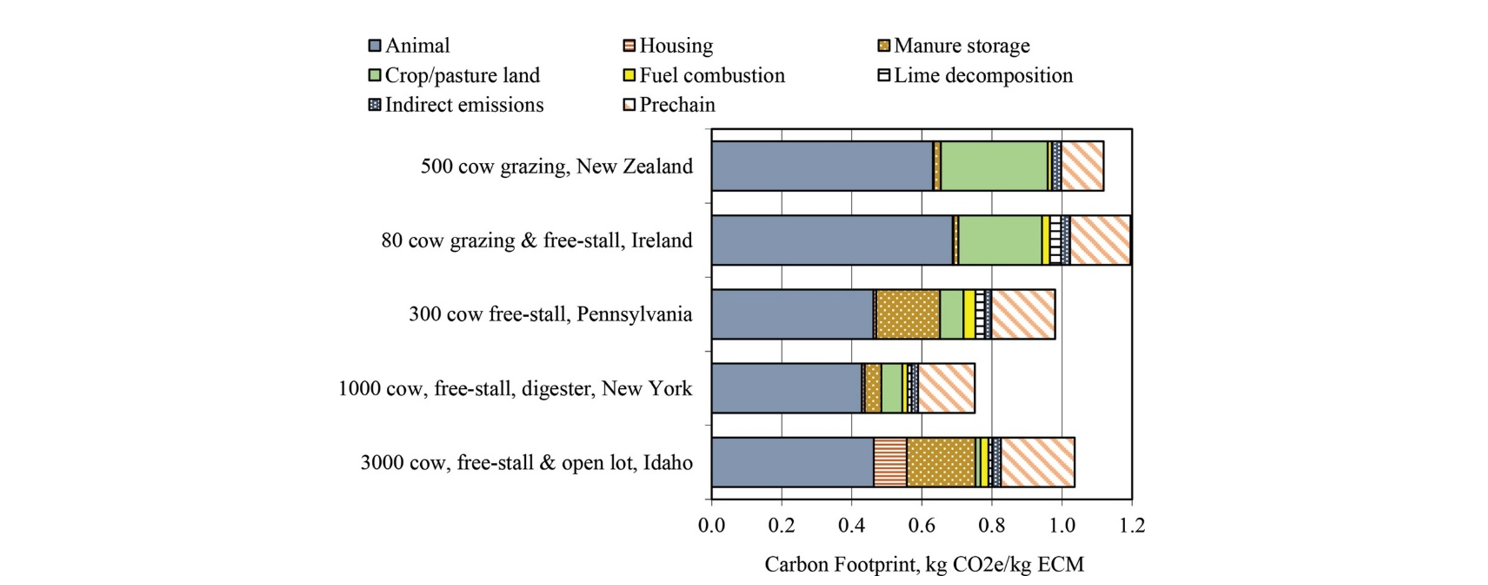

Arguably the most exciting thing about modern dairy is that it is one of the few agricultural systems that improves global sustainability simply by scaling current best practices. What do we mean by this? The global average production for dairy is 2,587 litres per animal per year, from a global dairy herd of ~264m cows. The best national production system in the world is the USA with ~10,500 kg of milk/animal/year. The dominant American production system also enjoys having the lowest GHG emissions per litre of milk in the world. However, as you can see in the table below there is a lot of variability to emissions based on farm type and milk production levels.

Table from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S002203021731069X#bib53

The general rule of thumb is that economies of scale matter and that free-stall/indoor systems generate less emissions per kg of milk produced (largely because pasture animals produce less milk with roughly the same amount of methane generation and use more land overall - even though most of this land is unusable for crops). Manure impact is drastically reduced by using anaerobic digestion, which is not possible on pasture systems.

It must be noted that the above table only shows emissions from the best commercial producers in the world. Relatively few global cows exist in such systems (ie, USA, NZ, and Ireland represent ~16.9m or 6% of the global herd). But we can take it that the best in class dairy system produces 0.75kg of CO2e/kg of milk or 21.4kg of CO2e/kg of protein, and that this is a replicable system (as evidenced by its ubiquity at national level in America).

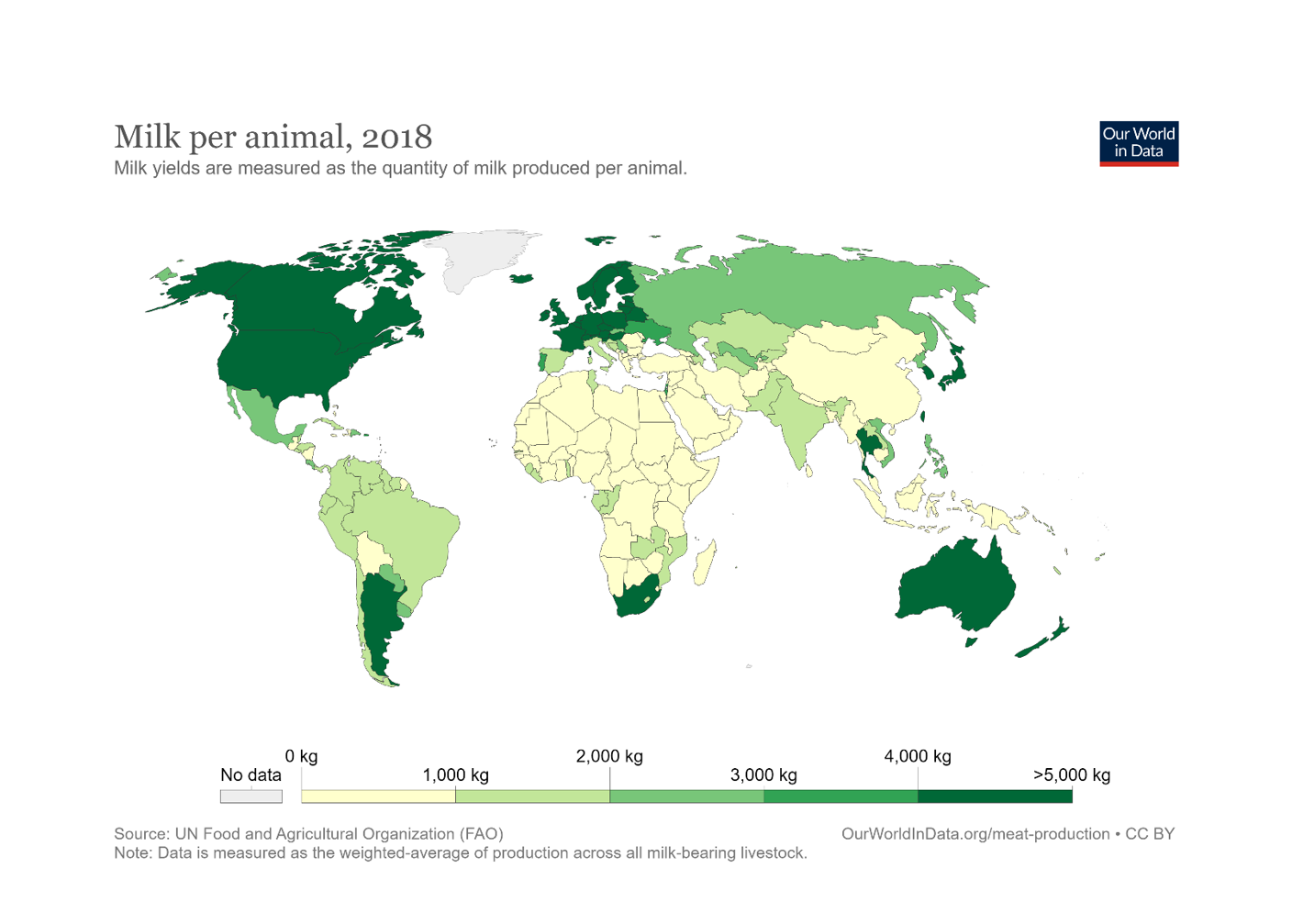

The country with the most cows in the world is India (~40m cows or 15.5% of the global herd), whose cows produce an average of 1,200 kg/animal per year. India’s emissions are 1.83kg of CO2e/kg of milk or 52.4kg of CO2e/kg of protein, more than twice what the most efficient system in the world produces. As you can see in the map below, most of the world’s cows exist in systems that are more like India than the USA. When we talk about mapping best practices, we are talking about getting the yields of places like India to the level of the USA by matching the dairy practices that produce such consistently high yields.

Let’s take a closer look at the history of milk production in the USA. In 1950, the US had 25 million dairy cows and 152m people. Today, there are slightly over 9 million cows (human population approx. 320M). With a much smaller herd today vs 1950, the US produces 60% more milk, which reduced the carbon footprint by approximately two thirds. The dairy farmers of America deserve tremendous respect and thanks for doing so much for the US’s food supply and carbon footprint.

While this transition took 50 years or so, the basic principles of it are relatively straight forward; improve genetics, use indoor production, access to modern feed additives, economies of scale, and tight animal husbandry/management. In Cainthus, we believe that technology can be used to map best practices from regions like the US to the rest of the world in a relatively rapid amount of time (as best evidenced by the modernisation of dairy in China, the gulf states, and Russia). Technology like Cainthus’ Alus can effectively provide a global level best practice audit system, where we can benchmark all dairy farms management practices against each other.

What does the dairy world look like if we assume that the anyone can produce dairy like America can? Global dairy production was 683 million tonnes of milk in 2018, provided by 264m cows, giving a yield per cow of 2,587kg/cow. If we assumed that every dairy produced like American dairies (10,500kg of milk/year/cow), then we would only need 68m cows globally, a reduction of 75% of today’s global cow numbers (and even far less than the 177m cows globally in 1961, the earliest year of FAO cow numbers). The GHG reductions are ~69%. These are outstanding numbers and offer a real opportunity to dramatically reduce global agricultural emissions. But it does not stop there.

The world record producing cow recorded 35,457 litres of milk in one year (https://www.dairyherd.com/article/how-wisconsin-dairy-raised-top-milk-producing-cow-world). While it is not feasible that we will get global production averages to such an extreme, it should be possible to get a 15,000kg/cow/year average yield by 2050. With that level of productivity, we would need a global herd of only 60 million cows to enable 10bn people to consume dairy at today’s global rate of consumption (~91kg of dairy/person/year), with a fraction of today’s GHG emissions and land use. And this is before we have even considered the use of new technologies, it is solely based on further scaling practices that are already widespread in global agriculture. There is so much more we can do to make dairy better than today’s best in class.

We readily concede that using best practices to reduce the global herd to <70m cows is easier to talk about than act on. India, for example, has a massively inefficient dairy system chiefly due to cultural and religious beliefs more than anything else. Similarly, much of sub Saharan Africa simply does not have the infrastructure required to produce milk at this scale. Professional milk production of this level will also make it impossible to produce dairy as a smallholder farmer, a major source of jobs and revenue in lower income countries.

However in the Covid-19 environment, it causes one to think about the fundamentals more than the “nice to haves”. What Ag systems should we stop supporting? What systems need more support? Should every country in the world have a domestic milk production system and the inefficiencies that come with this, or is it more important to produce as efficiently as possible from an environmental and economic perspective? Does it make sense to invest speculative capital in unproven alternative protein systems when we already have a system proven at global commercial level that simply needs more scaling?

Let’s hope we emerge from the Covid-19 crisis as a more pragmatic species that will seek to use the best tools to solve the biggest problems.